Edited from an Equal Exchange article; for the full article, please visit this link.

LIVE ZOOM EVENT: Pecans, Civil Rights, and Land Ownership: A Story of Cypress PondJoin a live conversation with Shirley Sherrod and Paul Jones to learn the rich and storied history of the movement to secure land rights and agricultural livelihoods for Black farmers in Southwest Georgia since the 1960s. How did systematic racial discrimination push Black farmers out of agriculture and land ownership, and how did a pecan growing project contribute to an enduring and powerful vision for justice? During two sessions this October, we’ll hear from Shirley and Paul firsthand and get a chance to ask questions and reflect on the ongoing work to sell these pecans under the Equal Exchange brand. Event 1: Wednesday, October 11, 2023, -

Event 2: Thursday, October 12, 2023, -

|

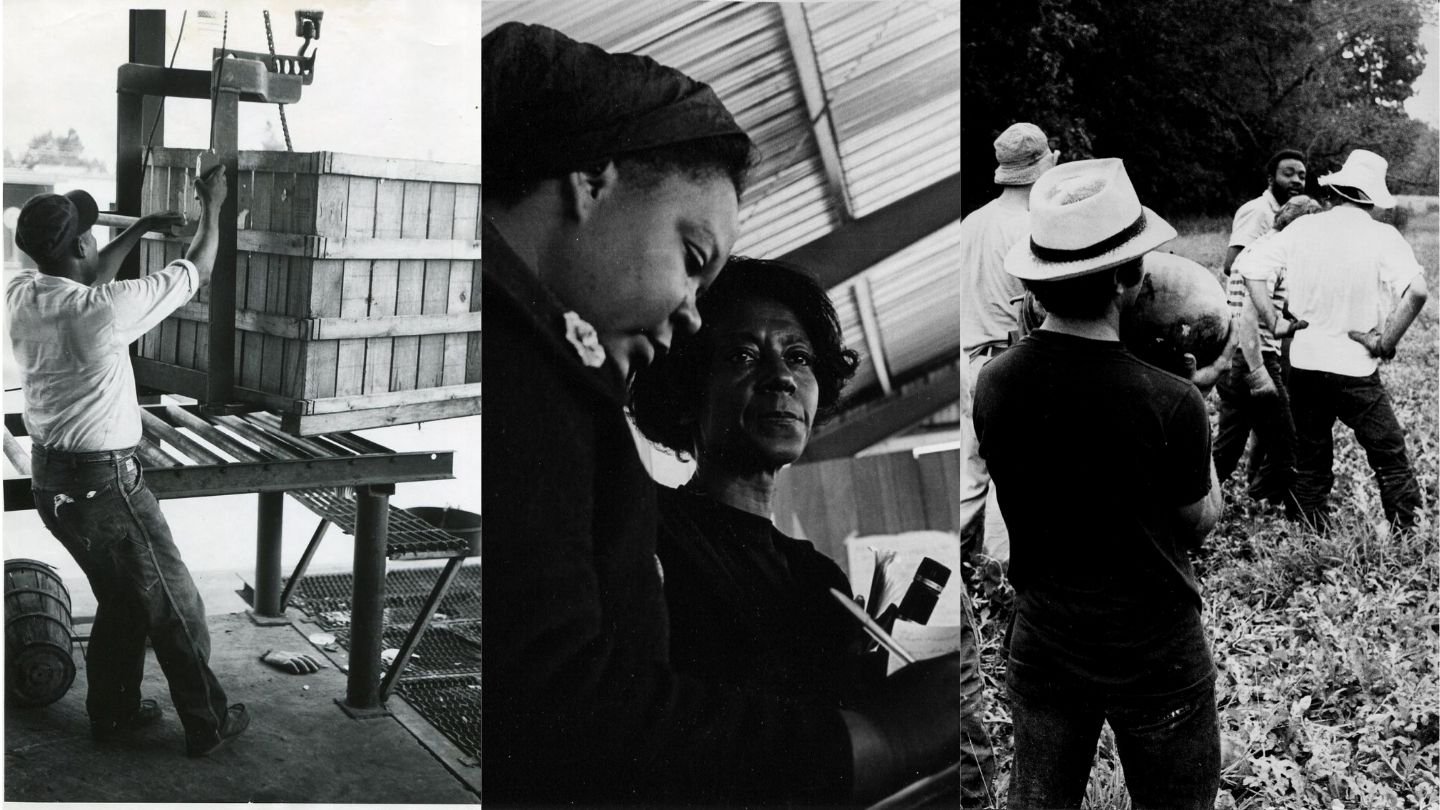

When you own the land you farm, you decide what to plant, when to harvest, and which maintenance methods to use. More importantly, you’re the one who controls your own livelihood. For Black farmers in the United States, land ownership is tied to freedom. But systematic racial discrimination has pushed many out of agriculture. Equal Exchange’s partners at New Communities, who supply our fair trade pecans, know the power of land—and these challenges—firsthand.

Land and justice for Black Americans

Shirley Sherrod, Vice President for Development at New Communities Inc., as well as former USDA Georgia State Director for Rural Development, says that coming out of slavery, Black people knew that owning land was important “to help lift the family out of poverty.” By 1910, Black people owned more than 14 million acres of land.

Shirley Sherrod, Vice President for Development at New Communities Inc., as well as former USDA Georgia State Director for Rural Development, says that coming out of slavery, Black people knew that owning land was important “to help lift the family out of poverty.” By 1910, Black people owned more than 14 million acres of land.

But holding on to their acreage and turning a profit has proved to be an uphill battle. Black farmers in America encountered—and still encounter—bias in countless ways, from institutions and from individual neighbors alike. Sherrod told us that farmers she knew weren’t able to depend on fair grading for crops like peanuts. Many processors wouldn’t work with them and buyers might offer artificially low prices. White dominance at all levels of government in the South meant that Black farmers’ interests were not protected. They faced discrimination from the banking system. They had a hard time accessing loans and credit. In consequence, they learned to rely on each other.

New Communities: Built together

New Communities, established in 1969, put cooperative values into action from the start. Shirley Sherrod says that she and the founders realized they needed to build something of their own in order to “use the skills they had to make life better.” They designated New Communities as America’s first community land trust; at almost 6,000 acres, it was the largest parcel of land owned by Black people in the whole country.

The Office of Economic Opportunity promised New Communities money and gave them a planning grant. But protests from white neighbors convinced the governor at the time, Lester Maddox, to veto federal money that might benefit their project. The local opposition they faced was constant.

The farmers persevered. By the early ’70s, they were selling watermelons to Safeway. But in the middle of the decade, drought hit the area. Like many of their white neighbors, New Communities applied to the Farmers Home Administration for an emergency loan. Unlike the applications of other farmers, theirs was denied. Multiple years with continuing drought was too much, and by 1985, New Communities was in foreclosure.

The role of the USDA

New Communities’ owners weren’t the only ones who had lost their land. In 1920, there were 925,000 Black-owned farms in the US, but by 1975, only 45,000 remained. Today, just 1% of rural land is owned by Black Americans.

In 1997, Black farmers filed a class action suit against the USDA, Pigford v. Glickman. They alleged that the agency’s allocation of farm loans and aid between 1981 and 1996 was unfair. The USDA admitted to having discriminated against Black farmers and settled, agreeing to a payout of $1.2 billion in the first phase and over $1 billion in the second phase. New Communities filed its own claim in 1999. The hearings, appeals and reviews went on for a full decade. Finally, in 2009, New Communities was awarded $12 million.

New Communities’ new start

Sherrod and others got busy finding land in the area of Albany, Georgia. They located Cypress Pond Plantation, 1,638 acres once owned by the largest slaveholder and richest man in Georgia. “I had some problems with that, initially,” Sherrod admitted, “but I got past it, because I started thinking, what a statement for our people, that this property can go from a slave owner to descendants of slaves.”

Pecan cultivation

Today, farmers at New Communities are growing satsuma oranges and Muscadine grapes for market. But pecans remain their major crop. Last year, Equal Exchange bought all of their pecan halves and helped find a buyer for the pieces that are a result of the shelling process.

Black Farmers’ problems aren’t over

Black farmers still confront bias today. Younger people who want to get into agriculture often have trouble acquiring land. “The fact is,” Sherrod says, “it’s hard to get a white farmer to sell to a Black farmer, even today, in this area.” And the problems with the USDA aren’t over. After the Pigford ruling, those who had been disadvantaged in the past were supposed to get priority, but it never happened, according to Sherrod. “Farmers who were successful with their claims were supposed to get debt written off.”

Moving toward healing

How does Sherrod envision the future for Black farmers and collective organizations like co-ops and land trusts? “We’re going to have to identify opportunities for finding definite markets, because our people have been taken down roads,” she says. “People aren’t crazy. They want to be able to work together. But they have to see that there’s a possibility for success.” She’s pleased to see “younger farmers beginning to come on board who don’t know all that bad history … willing to actually work together to make some exciting things happen.”